Frets Visits The Arthur E. Smith Banjo Company

By Mark Andrews

A.E. Smith tone chamber components

“We didn’t like either of our names for a banjo company,” said founding partner Kate Spencer. “Mark Surgies and I have the same last-name initial. We had a third partner at that time whose last name began with ‘M’ so we decided to call it the S&M Banjo Company. We even had checks printer up that way-and then we looked at them and said ‘Oh, my God.’”

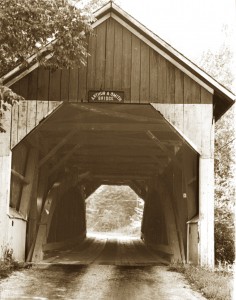

“There’s a funky little covered bridge west of here called the Arthur A. Smith Bridge. Mark drove over it one day and he liked the name. He even liked the design of the letters, so we decided to use it. We changed the middle initial to ‘E’ to give us some variety. The ‘E’ stands for everlasting.”

Kate had an early interest in playing banjo as, as did Mark. When she left college she worked for guitar maker Michael Gurian in Hinsdale, New Hampshire, doing guitar setups, neck fitting, brace shaping, and neck carving.

Meanwhile, Mark was making dulcimers in a shop of his own at the Leverett Craftsmen and Artists Center in Leverett, Massachusetts, that provide space and a common sales office for about 10 artisans.

Mark and Kate had known each other for some time when, one night as they were having dinner, they hit upon the idea of going into the banjo business. “It was just like a cartoon,” Kate recalled. “This little light bulb came on over my head and I said ‘Hey Mark, I’ve got a great idea. Let’s start a banjo company.’”

That was in October of 1973 and the company was launched the following January. Its starting assets amounted to $600 and a table saw. The company was headquartered in the Leverett Center for about four years, moving north to its present location at 30 Olive Street in Greenfield, Massachusetts, about a year and a half ago.

“We wanted to make an old-timey banjo that is equivalent to, but not a copy of, the best turn-of-the-century old banjos,” Kate told us. That old flavor is evident in their work. The Arthur E. Smith Banjo Company produces a line of meticulously crafted banjos that certainly reflects the respect and admiration Kate and Mark have for those early instruments. Banjos like classic Paramounts, Vegas, Coles, and S.S. Stewarts serve as the standards by which the makers at Arthur E. Smith measure their work.

When I asked Kate if she was trying to copy the works of those early makers, she replied, “No, we’re trying to create new instruments in that tradition-to create a new entity out of old quality and design concepts. Our peg head shape is reminiscent of Fairbanks, and our inlay patterns were influenced by Orpheum. Our laminating patterns are from S.S. Stewart. Early instruments have exerted a strong artistic influence on the Arthur E. Smith line”, she explains, “but have never been used as models for direct copies.

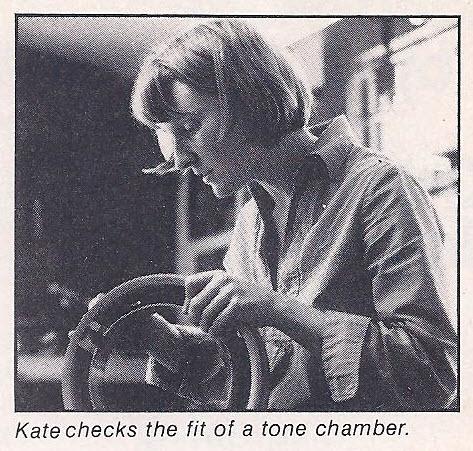

As I sat and watched Kate work on a banjo, I couldn’t help but notice her devotion. I wondered whether the instruments would just begin to seem like numbers after a while, and I asked her how she mixed her love for banjos with running a business.

“Well, we’re trying to mix the two,” Kate said, ”but mostly we’re doing this because we love banjos and we feel that we’re providing a service to this community. We’re not making any money out of it and I don’t know if we ever will. We manage to pay the rent and buy our materials, but there have been long periods of time when we have gone without salaries.”

Asked whether she could “feel” the personality of a banjo as she worked on it, Kate replied, “I feel the personality more in custom banjos, banjos somebody’s come to the shop to order. The custom banjos represent probably ten percent of the work we do here. But I still pay real close attention to every instrument, because we don’t mass-produce instruments. They’re all custom, in a way.”

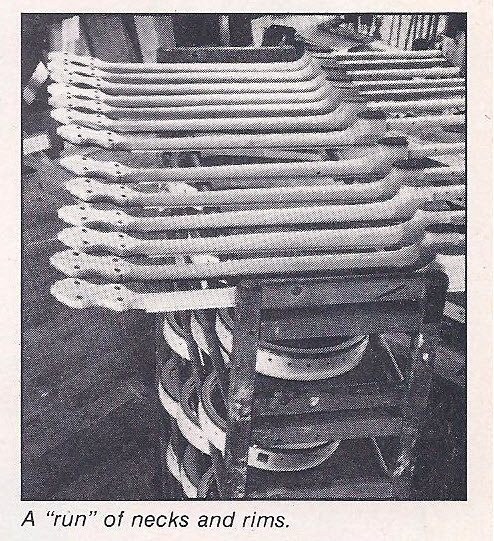

Even though the company doesn’t mass produce instruments, it still attempts to make components in batches or “runs”- doing all of the laminating at one time, or all the rough shaping at one time. Each run usually involved enough units for 40 banjos. After the rough work, the units in a run are divided into groups of approximately 13 parts each.

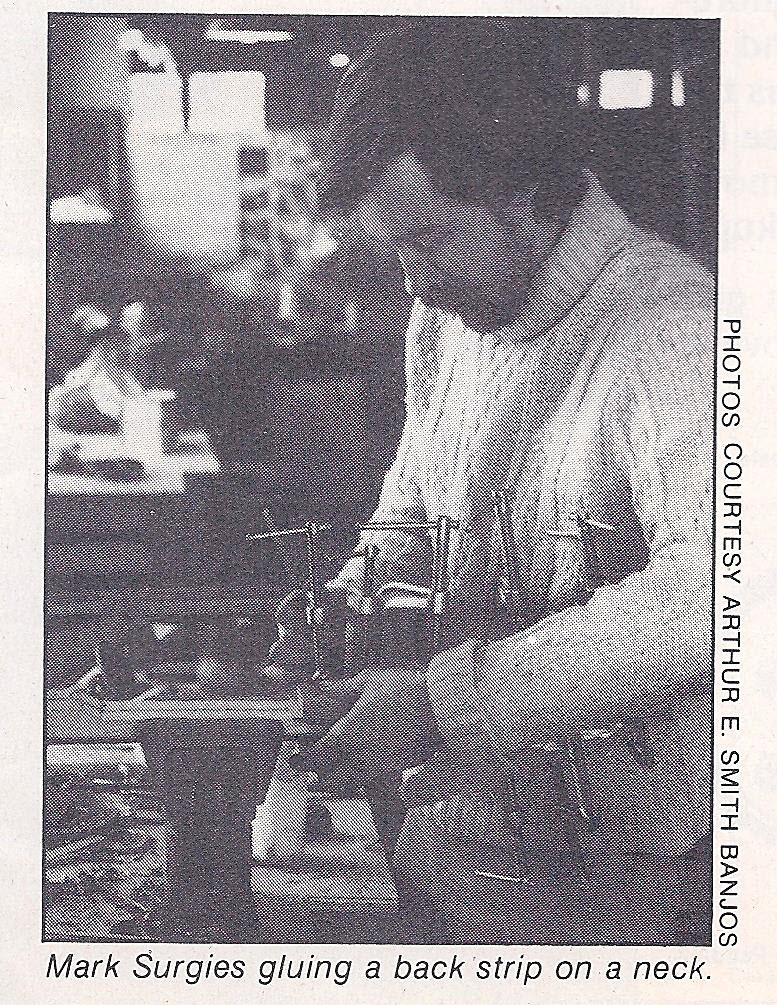

The banjo makers at Arthur E. Smith specialize in different production areas, with some overlap. Mark makes tools, fixtures and jigs, maintains the machinery, and is also responsible for a great deal of the design work. He cuts all the pearl, does some neck shaping, and performs all the lacquer spraying.

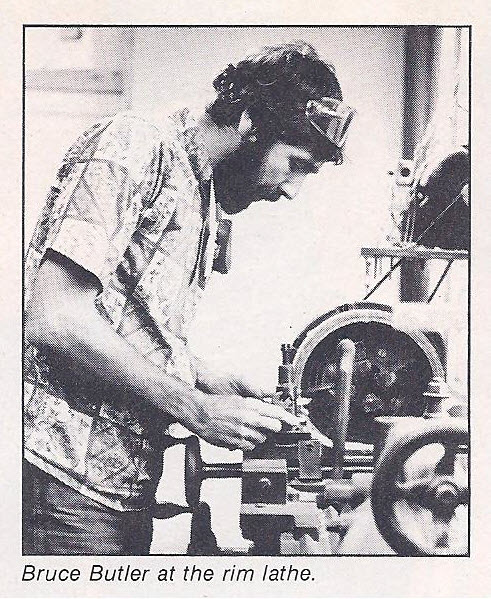

Bruce Butler makes all of the rims, doing the bending, laminating, machining, drilling and marquetry. He also does much of the wet sanding and compounds the lacquer finishes. Dave Doucet does the sanding and scraping, the neck laminating, and also helps Bruce with the lacquer compounding. Kate takes care of the instrument setups, and finishing touches, and shares heel-carving duties with Mark.

Kate does not expect that Arthur E. Smith Banjos will ever be a 200-employee shop. “I wouldn’t be making banjos then,” she told me. “I’d be telling other people what to do and I don’t want that. I want to work on the instruments. I want to make sure that they are right; I want to do the setups the fretwork, the bridges, the nuts and the strings, and put everything together. Mark plays each and every instrument before it goes out. He spends 15 to 20 minutes on each one, going over it, tightening the head again, just being sure it is right.”

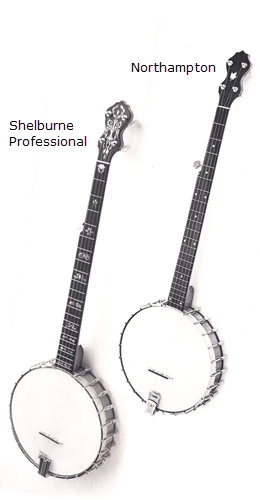

The Arthur E. Smith line offers there different models, each with a different tone-producing combination. The Northampton has a quarter inch brass rod- type tone ring between the rim and the head. The Maple Leaf has a three piece, hand spun tone system. The Shelburne is reminiscent of the Bacon Professional, featuring an internal resonator.

The company is currently designing a line of bluegrass resonator-type banjos that will echo the style and feeling of its old-timey models. They will probably incorporate the wooden dowel stick that is used in place of coordinator rods throughout the Arthur E. Smith line. Unlike the adjustable dowels found on Paramount banjos, the Smith Dowel stick is immovable. “We just set them up right in the first place,” Kate explained. “It doesn’t’ go anywhere.”

“We’ve seen many S.S. Stewarts with broken heels,” Mark noted. “That’s because they take that steel bar between the dowel stick and heel and crank it down, and bam! There goes your beautiful carved-roses Stewart heel. One reason we haven’t gone over to coordinator rods is that when you use them to adjust the neck angle you have to be bending the rim, and everything goes with it.”

The necks of all Arthur E. Smith instruments boast a heavy double truss rod assembly, with two 3/16” steel rods that work against each other to exert a bending force. Adjustment is made from the heel with a nut driver.

Arthur E. Smith also provides an unusual warranty for this day and age. “A banjo is guaranteed to its first owner for as long as they both shall live,” Kate told me. “We guarantee material and workmanship, which does not include string, head, and bridges. If anything goes wrong with the structural parts of a banjo-if it starts to come unglued, if the neck pulls up- we fix it at no charge. If somebody wants a major change in the action, depending on the circumstances, we’ll do it. If it’s our mistake, we correct it”

Nice people in New England. It’s a fine place to live, and fine place to visit, and a fine place to make musical instruments. It’s got plenty of beautiful scenery.

And it’s got that little covered bridge in Colrain.